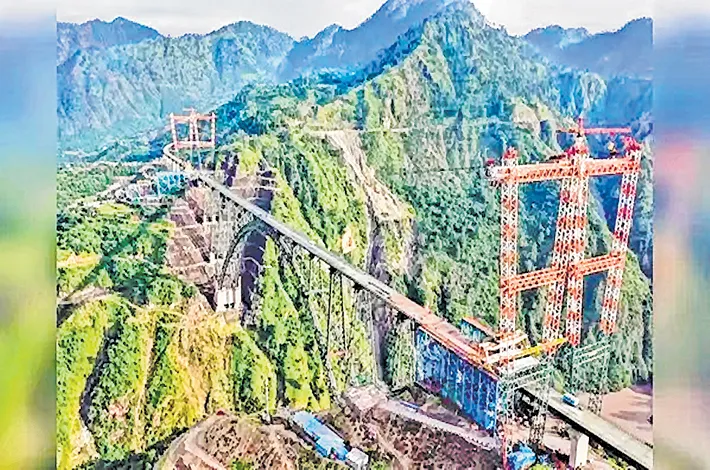

Chenab bridge faces safety questions ahead of R-Day launch

06-01-2025 12:00:00 AM

World’s tallest rail bridge bypasses mandatory load-deflection test and risks becoming a symbol of mismanagement

The Udhampur-Srinagar-Baramulla rail line, crucial for linking Kashmir to the rest of India, is set to be inaugurated for passenger services by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on January 26, 2025. However, concerns loom large as the Chenab Bridge—the tallest rail bridge in the world—has not undergone the mandatory load-deflection test, a critical safety measure.

Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw has touted the Chenab Bridge as 35 meters taller than the Eiffel Tower, but structural stability questions remain. The Shreedharan Committee had earlier raised alarms about the safety of the bridge, which spans a 359-meter-deep gorge.

The committee noted that the rock slopes on either side of the bridge were highly unstable, making it nearly impossible to ensure their long-term reliability, even with the best global design techniques.

Originally scheduled for completion in 2006, the bridge was delayed until 2024 due to these challenges. A trial run of an eight-coach passenger train was conducted on June 20, 2024, but no load-deflection tests have been performed.

These tests are vital for assessing a bridge's capacity to withstand heavy loads, earthquakes, high-velocity winds, and hydrological impacts.

Retired railway engineer Alok Verma has written to the Railway Minister, questioning the clearance of two sections of the rail line without conducting load-deflection tests on all new bridges, including the Chenab Bridge. Verma emphasized the importance of such tests, suggesting that four to six test trains should operate for at least 12 months to ensure the stability of bridges, tunnels, and other infrastructure.

The Kashmir rail link has already faced numerous setbacks. Misaligned tracks and collapsed bridges during construction led to massive cost escalations, from an initial estimate of ₹2,500 crore in 1994-95 to over ₹40,000 crore. The Chenab Bridge alone cost ₹14,000 crore. The 272-kilometer route includes 927 bridges and 38 tunnels, making it one of the most complex rail projects in the world.

Lawyer-activist Prashant Bhushan has sent a legal notice to the Railway Ministry, highlighting the high landslide risk in the Kashmir Himalayas. Bhushan pointed out that other major projects, like the Pamban Bridge and the Eastern and Western Dedicated Freight Corridors, conducted load-deflection tests before being operationalized.

He argued that bypassing such tests on the Chenab Bridge is a glaring safety lapse.

Bhushan also cited the Konkan Railway's history of landslide-induced accidents in 2003, 2004, and 2013, which claimed over 100 lives. “How can the Chenab Bridge be cleared without this critical safety assessment?” he asked.

Under growing scrutiny, Railway Minister Vaishnaw recently announced load-deflection tests on the Anji Khad Bridge, India’s first cable-stayed rail bridge. However, experts point out that these tests are elaborate and time-consuming, requiring three to six months to complete.

This raises questions about how passenger services on the Chenab Bridge can commence within three weeks.

“The failure to conduct thorough tests has already inflated costs,” said Verma. “Construction costs have soared to ₹400-700 crore per kilometer, 8-10 times the average for similar projects. The lack of adequate stations and loop lines further limits the line’s capacity, with only 8-10 trains expected to run daily, half the capacity of comparable routes like the Konkan Railway.”

The proximity of the Chenab and Anji Khad bridges to the Line of Control (LoC) also makes them potential targets for enemy attacks. If either bridge were to collapse due to earthquakes or sabotage, it could render the line inoperable for years. Geological challenges persist, as the line traverses a major fault zone, leading to 12 tunnel collapses during construction.

The project’s cost escalation—from an initial ₹1,500 crore for the Katra-Banihal section to over ₹40,000 crore—has sparked widespread criticism. Agreements between Indian Railways, the Konkan Railway Corporation Limited (KRCL), and IRCON allowed these companies to receive 10% of net profits for every rupee spent.

This incentivized prolonged construction timelines and inflated costs, as noted by the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) in 2010 and the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) in subsequent reports.

An internal Northern Railways report from 2012 revealed that public sector undertakings (PSUs) received 30-35% of construction costs as advance payments, with little oversight. These PSUs also earned additional profits, inflating project costs by 16-22%. Despite these findings, no corrective action was taken.

The Kashmir Rail Link is shaping up to be one of India’s most contentious infrastructure projects. While it promises to transform connectivity in the region, unresolved safety, geological, and financial issues threaten to overshadow its potential benefits. Without immediate corrective measures, the Chenab Bridge risks becoming a symbol of mismanagement rather than engineering triumph.